- Home

- Lipscomb, Suzannah

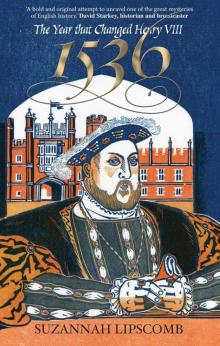

1536: The Year that Changed Henry VIII Page 3

1536: The Year that Changed Henry VIII Read online

Page 3

Yet, despite all this evidence of pleasure-seeking, martial ambition and youthful zest, it would be wrong to conclude that this exuberant and boisterous young king was always happy-go-lucky. He could at times, even in his early years, be wilful, stubborn and obstinate. Wolsey wrote of Henry that ‘rather than… miss or want any part of his will or appetite, [the king] will put the loss of one half of his realm in danger’, and warned a potential member of the privy council to ‘be well advised and assured what matter ye put in his head; for ye shall never pull it out again’. He testified to having spent hours on knees pleading with Henry to dissuade him from one or other course of action, to no avail. Ironically in light of later events, one issue on which Henry was dogmatic in this period was orthodox Roman Catholic religion. In 1521, in response to Martin Luther’s De Captivitate Babylonica, Henry VIII, undoubtedly with some help, wrote a polemical book called Assertio Septum Sacramentorum (In Defence of the Seven Sacraments) defending papal authority and condemning Luther. This book, which sold remarkably well, earned him the title Defensor Fidei or Defender of the Faith.11

Perhaps Henry’s tendency towards obstinacy was partly a result of his ideas about how a king should be. Despite relying on his ministers, Henry seems to have believed that he should rule as well as reign. He once told Giustinian that ‘things uncertain ought not to escape the lips of a king’, and later was reported as saying that ‘if I thought my cap knew my counsel, I would cast it into the fire and burn it’ – indications that he believed he should be firm, decisive and self-reliant. While it was not a common occurrence during his youth, he also was at times reported to ‘wax wrath’, suggesting that the obduracy and temper of his elder years were latent, though not catalyzed nor fully developed at this stage. Another quality that would be exaggerated with his passing years was his pronounced sense of his own importance, even in the context of far greater European powers. In 1516, he bragged to Giustinian that ‘I have now more money and greater force and authority than I myself or my ancestors ever had; so that what I will [wish] of other princes, I can obtain’. Interestingly, what does not seem to be apparent in these years is the ‘strong streak of cruelty’ that at least one historian has suggested as a constant quality to Henry VIII: such cruelty was only really exhibited from around the mid-1530s, especially in and after 1536.12

CHAPTER 3

The Divorce

Despite his earlier love for her, from around 1527, Henry VIII sought to separate from Katherine of Aragon after nearly twenty years of marriage. This was in large part because, although Katherine had been pregnant six times, the couple had suffered a series of heartbreaking miscarriages, stillbirths and cot deaths, and only one daughter, Princess Mary, had survived. Although Henry had an illegitimate son by his former mistress, Elizabeth Blount, in 1519, he had good reason to want a legitimate heir. Henry – and most people at the time – believed that one of his principal responsibilities as king was to produce an adult male heir, that is, a boy of at least fifteen years old, who could succeed peacefully when Henry died, to secure the dynasty. It was feared that if one of his daughters became queen then their marriage to another king or prince would mean England would be ruled, or dominated, by a foreign power. Children could not rule as monarchs themselves; their powers were given to individual regents or groups of councillors, and disputes over a regency could be very bloody, endangering the security, peace and prosperity of a country. The Tudor dynasty was still very new and far from securely rooted, having been established by Henry VII’s victory at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. Henry VIII – and the country – wanted a secure line of princes to ensure that the turmoil of a contested throne did not occur again. He worried that if he didn’t have one or more legitimate sons by his early thirties, then he might easily die in his fifties without an adult male heir (he had good reason to worry – his grandfathers had died at twenty-six and forty-one; his own father at fifty-two). And even one son was no guarantee of a smooth succession, as the death of Henry’s elder brother, had shown.1

This very real anxiety about the lack of a male heir suggests that Henry was genuine in his conviction that his lack of a surviving legitimate male heir meant that he was, in some way, being punished by God, and that the Pope should never have given him the dispensation that allowed him to marry his brother’s widow. This realization coincided with the discovery of the witty, captivating Anne Boleyn. Although not particularly beautiful, Anne had unusual dark hair, fine eyes, a certain grace and seemed sophisticated because of her time at the French court. Before long, Henry ‘began to kindle the brand of amours, which was not known to any person’.2

Henry probably first noticed Anne around Easter 1526, and he began seeking a divorce in 1527. It is important to note that Henry wanted to marry Anne, and would not accept any alternative. The traditional explanation for why Henry was determined to marry her, rather than take her as his mistress, is that Anne refused to consummate their relationship before marriage. The evidence of their letters suggests that there was some level of sexual play between the couple, but it is very likely that they did wait six or seven years before having intercourse. In an age before any reliable contraception, the fact that Anne did not give birth until September 1533 suggests that they had simply abstained for many years. Yet the decision to marry Anne was prompted by more than Anne withholding sex (the abstinence may even have been mutual). Henry, throughout his life, liked things to conform to the letter of the law. He wanted the world to be recast as he saw it. In this, he wanted it to be declared that it had never been right for him to marry Katherine of Aragon, and that it was therefore right for him to marry Anne Boleyn. He wanted, above all, legitimacy and exoneration. According to his own testimony, he did not wish to take another wife ‘for any carnal concupiscence, nor for any displeasure or mislike of the Queen’s person or age’, but because of a ‘certain scrupulosity that pricked my conscience’.3

Henry staked his challenge to the validity of his marriage to Katherine on two arguments:

* That the union of a man and the wife of his brother was contrary to the law of God, according to Leviticus 18:16 and 20:21, and that no papal dispensation was sufficient to permit it.

* That the specific dispensation granted by Pope Julius II was invalid because of certain technical irregularities, especially where the deliberate insertion of the word forsan (perhaps) made it unclear whether or not the marriage between Katherine and Arthur had been consummated.

There were a few minor problems – such as the fact Henry and Katherine weren’t actually childless, just had not had a surviving male child, and above all, that Deuteronomy 25:5 stated the polar opposite of Leviticus: that if a man died without children, ‘the wife of the dead shall not marry without unto a stranger: her husband’s brother shall go in unto her, and take her to him to wife, and perform the duty of an husband’s brother unto her.’ The real crux of the matter rested on whether or not Katherine had been a virgin, as she claimed, when she remarried, a fact impossible to verify either way. So Henry gathered a team of theological experts, led by Thomas Cranmer, to study the scriptures for him, bolster his position and garner the support of the universities of Europe. Nevertheless, the theological ambiguities of his case meant it could never be watertight, and anyway, Pope Clement VII was not a free agent. The response he could give depended a lot on his relationship with Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, Katherine’s nephew.4

Henry needed an alternative strategy, and that strategy could be found in the increasing warmth Henry felt towards the ideas of royal supremacy and divine-right kingship. Historian J. J. Scarisbrick was so convinced that Henry’s growing commitment to the principle of the royal supremacy paralleled the divorce crisis that he asserted: ‘if there had been no divorce Henry might yet have taken issue with the Church’. The English crown had always subscribed to the notion of the divine right of kings to rule, as their motto since 1413, Dieu et mon droit, emphasized. Henry’s assumption of the title of Supreme Head of the Chur

ch of England took this a stage further. Henry grew convinced of his unique position as God’s anointed deputy on earth, believing that the Supreme Headship was his birthright, and expecting others to believe it too. Even before the 1530s, Henry showed signs of believing in his position directly under God: in November 1515 at Baynard’s Castle, he declared that ‘by the ordinance and sufferance of God we are king of England, and the kings of England in time past have never had any superior but God alone’. Then, at some point after 1528, Anne Boleyn had given him a copy of William Tyndale’s The Obedience of a Christian Man, an evangelical work which asserted that it was shameful for princes to submit to the power of the church and an inversion of divine order. Tyndale stressed it was the king, and not the pope, who was ordained by God to have no superior on earth, and kings must be obeyed, for they give account to God alone. Henry said it was ‘the book for me and all kings to read’. It is vital to realize that for Henry, the royal supremacy, and his direct position under God became a firm conviction, and like all his firm convictions, it was not easily moved.5

The scholars examining the case for divorce reached the conclusion that England was an empire, which, in the language of the time, meant that English kings had always enjoyed spiritual supremacy in their dominions and possessed a sacral kingship. The first indication of Henry’s belief in his rightful role as Supreme Head in his own country came in August 1530 when Henry asserted that no English man could be summoned out of his homeland to a foreign jurisdiction (in other words, to a divorce court in Rome). It was also in 1530 at Hampton Court that Henry, having summoned a council to discuss his divorce, decided to inform the Pope that he had no jurisdiction in the case, though it took another three or four years for the royal supremacy to be completed. The logical result of this came in April 1533 when parliament passed the Act of Restraint in Appeals forbidding appeals to Rome, which stated that ‘this realm of England is an empire, and so hath been accepted in the world, governed by one supreme head and king’. In May 1533, convocation of the English clergy and Thomas Cranmer, newly appointed archbishop of Canterbury, declared Henry’s union with Katherine of Aragon null. But Henry had in fact already married Anne Boleyn – twice – officially in January 1533 and secretly before that, in November 1532. On 11 July 1533, the Pope condemned Henry’s separation from Katherine and gave him until September to take her back under threat of excommunication. Henry ignored this, and in September, Anne gave birth to a healthy girl, whom they named Elizabeth, after their mothers.

Meanwhile, progress towards the royal supremacy continued. In early 1534, an act of parliament halted all payments to Rome and granted the king permission to appoint bishops, and most importantly of all, the 1534 Act of Supremacy finally declared that Henry was and had always been the Supreme Head of the Church of England. The Anglican Church had been created. A public persuasion campaign was mounted through the pulpit and printing press, and from June 1535, bishops were ordered to preach on the royal supremacy each Sunday.6

But this was not enough to satisfy Henry. The whole nation was required to be complicit in the king’s decision. The Act of Succession, also passed in 1534, stated the lawfulness of Henry’s marriage to Anne Boleyn and that their children would be true heirs to the throne and all English subjects were required to swear an oath agreeing this. The oath read: ‘to be true to Queen Anne, and to believe and take her for the lawful wife of the King and rightful Queen of England, and utterly to think the Lady Mary daughter to the King by Queen Katherine, but as a bastard, and thus to do without any scrupulosity of conscience’. Among the laity and episcopacy, only Sir Thomas More and John Fisher, bishop of Rochester, refused to swear. Henry’s overarching commitment to the principle of royal supremacy must explain the vehemence of his response: both were sent to the Tower of London and Henry deliberately passed the Act of Treason, which came into effect in early 1535 and promised death for anyone ‘maliciously denying the royal supremacy’. As a result of this act, in June 1535 Fisher and More were both beheaded. Their execution, particularly Fisher’s (as a bishop), shocked the world. The separation from Rome was complete.7

For Henry, there was a significant degree of ‘religion’ in his decision to break with Rome. It was manifested in the way he saw his relationship with Katherine, as one punished by God for living outside the law. It was also apparent in his dedication to the notion of the royal supremacy and to his divine-right kingship, under God, which committed him to the righting of religious abuses in the church, and the ‘cure’ of his people. With Anne Boleyn at his side, Henry had been exposed to evangelical thought, especially that which gave primacy to princes over prelates, and had, perhaps inadvertently, opened the door to the reformed ideas of continental Europe. For Anne Boleyn deserves a little more mention in this story. As we have seen with her apparent refusal to sleep with the king, by her gift to Henry of important evangelical works such as Tyndale’s The Obedience of a Christian Man, and not least by her charm and attractiveness, Anne Boleyn’s influence on the king was great. Influence on the king meant influence in the country. Anne used her position to become an ardent patron of the evangelical cause. She was a major importer of evangelical books and she had ‘the perfect opportunity to promote evangelical activists after an extraordinary crop of deaths of distinguished elderly bishops who might have proved awkward obstacles for the evangelical cause.’ Between 1532 and 1536, nine bishops died, eight of which were apparently due to natural causes (Fisher, as we have noted, was beheaded); and there were also two resignations. Many of their replacements were Anne’s evangelical clients. Her power was such that the imperial ambassador, Eustace Chapuys, declared her displacement by Jane Seymour would be ‘a remedy for the heretical doctrines and practices of the concubine – the principal cause of the spread of Lutheranism in this country’.8

Yet, on the eve of 1536, Anne Boleyn’s star was in the ascendant, and Henry VIII enjoyed a powerful position, full of hope for the future. He had been on the throne twenty-seven years, and for much of that time, he had been highly and fulsomely praised. His wife, who had two and a half years before given birth to a healthy little girl, was three months pregnant, and Henry had strong hopes that this time, Anne would bear him a son and heir. Six months earlier, Henry had eradicated opposition to his new position of Supreme Head of the Church of England, by silencing permanently those who refused to acquiesce, such as John Fisher and Sir Thomas More. His illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond and Somerset, was a strong lad of seventeen in whom Henry took much joy. The only fly in the ointment was that his ex-wife, Katherine of Aragon, the Princess Dowager, lingered at Kimbolton Castle in Cambridgeshire. As a result of her degraded position, her nephew, Charles V, emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, was a constant, if latent, threat to the security of England. Yet, in 1536, Henry VIII would have had good reason to hope that all things would finally be well. In actual fact the opposite was true; this year would, in many ways, be his undoing.

CHAPTER 4

1536 and All That

Historians have noted that that 1536 was a particularly awful year for Henry. Derek Wilson calls it Henry’s ‘annus horribilis’. R. W. Hoyle refers to it as ‘the year of three queens’, and Sir Arthur Salisbury MacNulty concludes that, in reaching forty-five, ‘it is justifiable to regard the year 1536 as marking the approach of Henry’s old age’. Few, though, have connected this turbulent and important year with Henry VIII’s changing character. Only Derek Wilson has noted that ‘most of the reign’s acts of sanguinary statecraft’ occurred after this point, and that ‘it was in 1536 that bloodletting of those close to the Crown became frequent’.1

A brief chronological overview, however, of the many tumultuous events in the life of Henry VIII in 1536 begins to suggest the significance of this one year.

The year began, from Henry’s perspective, well. On 7 January, Katherine of Aragon, Henry’s estranged (and denied) first wife, died. Yet, only a couple of weeks later, a series of less propitious acts occurred. Henr

y fell from his horse while jousting. He was unconscious for two hours and observers feared the worst. Despite the official pronouncements of his rude health, the fall appears to have burst open an old injury which would never properly heal and meant that this great athlete of the tiltyard would never joust again.

Anne Boleyn attributed her shock at the king’s fall to the next major event of 1536. She miscarried on the day of Katherine of Aragon’s funeral – and it had been a boy. This was a huge disappointment to the king, and threatened the stability of the realm at a time when English security was already in jeopardy. In early 1536, an edict issued by the Pope that would have deprived Henry of his right to rule was circulating in Europe, and only needed to be formally published for the invasion and overthrow of Henry’s throne to become legitimate.

In March 1536, parliament passed an act that was to have enormous repercussions – the Act for the Dissolution of the Smaller Monasteries. At the same time, Henry received a book, written by Reginald Pole, his own cousin, which viciously attacked Henry’s role as the Supreme Head of the Church of England.

The most shocking incident of the spring was, however, the ‘discovery’ of Anne Boleyn’s apparent adultery with a number of men of the King’s Privy Chamber, and her arrest, trial and, finally, execution on 19 May. The king lost no time in remarrying: on the day of Anne’s death, Archbishop Cranmer issued a dispensation for Henry to marry Jane Seymour; the couple were engaged the following day and married ten days later, on 30 May. Perhaps to mark their union, around this time, Hans Holbein the younger painted portraits of the pair. The one of Henry, known as the Thyssen portrait, is a stunning departure from previous portraits of the king; the power and magnificence exuded by Henry in the image is striking, starkly contrasting with the reality of the fact that Henry turned forty-five on 28 June 1536 – an age reckoned by the standards of the sixteenth century to represent old age.

1536: The Year that Changed Henry VIII

1536: The Year that Changed Henry VIII