- Home

- Lipscomb, Suzannah

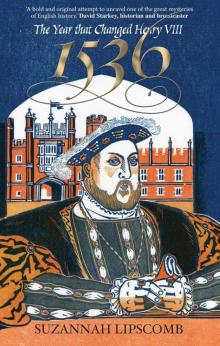

1536: The Year that Changed Henry VIII Page 5

1536: The Year that Changed Henry VIII Read online

Page 5

Anne Boleyn claimed that king’s fall was of even greater importance. On 29 January 1536, Anne miscarried, blaming the miscarriage on her shock at hearing the news of the king’s fall five days earlier. It was Chapuys who reported this and he was scathing about her reasoning. But at least two other sources confirm this. The chronicler and Windsor herald, Charles Wriothesley, wrote that ‘Queen Anne was brought abed and delivered of a man child… afore her time’, because ‘she took a fright, for the King ran that time at the ring and had a fall from his horse… and it caused her to fall in travail’. In addition, Lancelot de Carles, who was staying in London, composed a French poem on 2 June 1536. It reiterates how the king fell so severely from his horse that it was thought it would prove fatal, and that when the queen heard the news, it ‘strongly offended’ her stomach and advanced ‘the fruit’ of her womb, so that she gave birth prematurely to a stillborn son.6

It is almost certain that this fall had a major impact on Henry’s health that would affect him ever after. During one of his royal progresses in 1527, Henry had suffered from a ‘sore leg’, which seems likely to have been a varicose ulcer on the thigh. It was, at least temporarily, successfully healed by Thomas Vicary, who was appointed the king’s surgeon in 1528, no doubt in recognition of his services. The fall of 1536 probably caused the ulcer to burst open. This time, however, Vicary seems to have been unable to cure it, despite the fact that he was finally made Sergeant-Surgeon in this year, a timing which may have been more than mere coincidence. That this ulcer was to plague Henry chronically throughout the rest of his life is made clear in a letter from John Hussey to Lord Lisle in April 1537 which noted ‘the King goes seldom abroad, because his leg is something sore’, and in June that same year, Henry himself wrote to Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, that the real reason for postponing his trip to York was ‘to be frank with you, which you must keep to yourself, a humour has fallen into our legs, and our physicians advise us not to go far in the heat of the day, even for this reason only’. A year later, one of the fistulas in his leg became blocked, and the French ambassador, Louis de Perreau, Seigneur de Castillon, noted that ‘for ten or twelve days the humours which had no outlet were like to have stifled him, so that he was sometime without speaking black in the face and in great danger’. Later that year, Sir Geoffrey Pole, in his examination under the charge of treason, said, ‘that though the King gloried with the title to be Supreme Head next God, yet he had a sore leg that no poor man would be glad of, and that he should not live long for all his authority next to God’. After a similar attack in 1541, the new French ambassador, Charles de Marillac, made a passing reference that further confirms that the king’s leg had put him in great peril from around 1536, although it seems not to have been much publicized at the time. Marillac wrote in March 1541 that there was a complication with the ulcer for ‘one of his legs, formerly opened and kept open to maintain his health, suddenly closed to his great alarm, for, five or six years ago, in like case, he thought to have died’. The diagnosis of the exact nature of the ulcer has been debated. Early suggestions that it was a luetic – or syphilitic-ulcer, do not correspond well with the fact that the king showed no other signs of syphilis and that syphilitic ulcers are inclined to self-heal. Sir Arthur Salisbury MacNalty suggests that Henry suffered from osteomyelitis, a chronic septic infection of the thigh bone, and that the episode of 1541 may have been a thrombosis vein with detachment of the clot causing pulmonary embolism, with intermittent fevers thereafter as a result of septic absorption from the wound, as for example, in 1544. It is also possible that such an attack was the cause of Henry’s death, although Sir Arthur indicates that ‘uraemia due to chronic nephritis with a failing heart and dropsy cannot be excluded’.7

The ulcer produced increasingly frequent and severe pain, infections and fevers and discharges that let off an embarrassingly unpleasant smell. The combination of this recurrent and excruciating pain, together with the unprepossessing nature of his running sore, seems to have gradually manifested itself in the personality of the king. Henry became increasingly anxious and irascible, easily irritated and prone to rage. As we’ll see, there were other factors in this shift in his character, but the impact of this draining and debilitating pain should not be underestimated.

Although Henry continued to hunt, the pain in his leg meant that he was never able to joust again. 1536 effectively spelled the end of his active life, and with it, the beginnings of his obesity. In 1536, Henry’s waist measured 37 inches, and his chest 45 – an increase from his 23-year-old measurements of 35 and 42, but still a fine figure for a man in his mid-forties (and still keeping roughly the same waist-chest ratio as in 1514). Yet by 1541, only five years later, he had become enormous – with a waist measurement of 54 inches, and a chest measurement of 57. While this may not be exceptionally obese by modern standards, at six foot two, Henry already towered over his contemporaries (the average adult male was about 5 foot 7½ inches), and was now gross, compared with his peers. In a letter of October 1540 Richard Pate, the archdeacon of Lincoln, reported from Brussels the European gossip that the king had ‘waxen fat’ while Marillac in 1541 noted that Henry was very stout (‘bien fort replet’). Eventually, his obesity was such that he had to be moved around his palaces in some form of carrying-chair. This was quite a come-down for one who had been eulogized as a young man for his athleticism and good looks. Giustinian wrote in 1515 that ‘His Majesty is the handsomest potentate I ever set eyes on’, and went on to rhapsodize that Henry was ‘above the usual height, with an extremely fine calf to his leg, his complexion very fair and bright, with auburn hair combed straight and short, in the French fashion, and a round face so very beautiful, that it would become a pretty woman’. Thomas More remarked that, ‘among a thousand noble companions, the King stands out the tallest, and his strength fits his majestic body. There is fiery power in his eyes, beauty in his face, and the colour of twin roses in his cheeks.’ Henry, at this time, was the fulfilment of Castiglione’s description of the appearance of the ideal courtier: ‘I wish our courtier to be well built, with finely proportioned members, and I would have him demonstrate strength and lightness and suppleness and be good at all the physical exercises befitting a warrior’.8

The psychological impact of the fall is more difficult to measure than the physical, but it is not hard to imagine the effect that massive obesity might have had on one so formerly praised for his masculine beauty. In addition, if physical strength was understood by the sixteenth century to be a key yardstick of masculinity, then it is a fair assertion that for a man who had been so publicly acclaimed for his prowess at the tilt, his inability to pursue such activities after this point must have had a deep emotional impact. Until this time, ‘he never attempted anything in which he did not succeed. He had such natural dexterity, that in the ordinary accomplishments of throwing the dart, he outstripped everyone’, Erasmus noted in 1529. Now, he had met with disability. According to historian Lyndal Roper, sixteenth-century masculinity drew its power from ‘rumbustious energy’: the ‘figure who epitomized masculinity’ was the ‘man of excess’ in his strength, courage, display and riotousness. Henry had been such a man, and although, as we shall see, Henry compensated for his lost manhood in display, he no longer possessed any of the ‘rumbustious energy’ of his youth.9

Essentially, the fall marked, for Henry, the onset of old age. In the same year he turned forty-five. To understand the significance of this, it is important to realize that the sixteenth century conceived of ageing as a series of stages. The ‘ages of man’ moved from childhood to adolescence, from adolescent to youth, from youth to manhood and from manhood to old age. Different medical tracts assigned different ages to these stages: the most pessimistic considered ‘the lusty stage of life’ to last from twenty-five to thirty-five, followed by old age. Elyot’s Castle of Health, published in 1561, was slightly more optimistic, stating that old age began at forty, but even the most upbeat categorization placed it no later than

fifty. Turning forty-five certainly marked the onset of this new phase for Henry. Prospero, in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, is in his mid-forties, but throughout the play, references are made to his advancing age and declining abilities.

It wasn’t all bad, however. As scholar Keith Thomas points out, early modern society was gerontocratic – it was ruled by men in their forties and fifties. Such men were thought to possess the right measure of humours, which dried up their strength but made them calmer, more sedate and, therefore, more wise. But this society was also gerontophobic. There were lots of anxieties and insecurities around old age – chiefly to do with powerlessness, the stripping away of health and respect, and becoming the scorned stereotype of ‘Old Adam’, the ‘doddering old man… being cuckolded by his lusty young wife’. Old age was universally regarded as ‘itself a disease’, ‘a perpetual sickness’, and ‘the dregs… of a man’s life’.10

One piece of evidence suggests that the diminishing effect of the events of 1536 on Henry’s youth and manhood would have been magnified by latent concerns. In May 1535, Henry VIII had caused his beard ‘to be knotted and no more shaven’, and at the same time, he polled his head and commanded the court to adopt a similar fashion – a closely cropped style. The permanent adoption of a beard is very significant. In a fascinating article, Will Fisher suggests that ‘in the Renaissance, facial hair often conferred masculinity: the beard made the man’. He points out that virtually every man depicted in portraits in the century after 1540 sported some kind of facial hair. Texts of the period corroborate the association of a beard with manliness. Again and again, treatises reiterate that a beard is ‘a sign of manhood’, ‘the natural ensign of manhood’, or as explained by Johan Valerian in 1533, ‘nature hath made women with smooth faces, and men rough and full of hair’, therefore ‘it beseemeth men to have long beards, for [it is] chiefly by that token…[that] the vigorous strength of manhood is discerned from the tenderness of women’. Finally, facial hair, was in medical textbooks of the time strongly linked to the production of semen. In other words, a beard was a mark of ‘procreative potential’. Henry VIII’s decision to wear a beard and be ‘no more shaven’ was therefore a powerful assertion of his masculinity and ability to father children. It suggests that there were pre-existing anxieties about his manhood, naturally associated with his continuing lack of a legitimate son, that were ready to be activated into full-blown paranoia and reaction by the turn of events just one year later. Interestingly, at the same time, Henry VIII introduced laws on the wearing of beards by commoners. In April 1536, Henry VIII commanded the newly-conquered town of Galway that men’s ‘upper lips [were] to be shaven’. This colonial injunction suggests that Henry knew that there was a power in stripping a man of his beard. There has also been a suggestion that in 1535, Henry VIII ordered a tax on the wearing of beards, though this remains unverifiable. Nevertheless, the Irish law – and this alleged tax – indicate both Henry’s latent insecurity and his assertion of his pre-eminent manliness.11

CHAPTER 7

The Fall of Anne Boleyn

Henry’s fall from his horse thus provided the context, and according to Anne Boleyn, the catalyst, for the first of a further series of events in 1536 associated with Henry’s family and marital life.

On 29 January, the day of Katherine of Aragon’s funeral, Anne Boleyn miscarried of a male foetus. The significance of this miscarriage has been the subject of great discussion among historians. Many commentators have suggested that Anne’s miscarriage inexorably led to her downfall – for only four months later, she was executed and the king remarried. Had she, in the words of Chapuys, ‘miscarried of her saviour’? Was the miscarriage, as David Starkey suggests, ‘the last straw’? Or was her undoing the result of a more complex set of causes?1 Had, for example, Henry and Anne’s relationship gone into terminal decline, and what was the role of Jane Seymour in this? Did Henry knowingly and monstrously invent the charges of adultery against Anne, or did he allow himself to be deceived? Was it Cromwell who was responsible for Anne’s demise? Or was she simply guilty of the charges laid against her?

Anne’s Miscarriage

We should first consider whether Anne’s miscarriage marked the beginning of the end for the queen. The issue is confounded by the fact that Anne may or may not have miscarried two years earlier, in 1534. Anne had given birth to Elizabeth eight months after her official marriage to Henry in January 1533, and ten months after Anne and Henry’s secret wedding, recorded by chronicler Edward Hall in mid-November 1532. Becoming pregnant so swiftly after beginning sexual intercourse and bearing a healthy child boded well. In 1534, there were again signs of a pregnancy and observers commented on it. Chapuys noted that Anne was pregnant in late January 1534 and George Taylor, in a letter to Lady Lisle in April, remarked that ‘the Queen hath a goodly belly’. This comment implies Anne’s pregnancy was visible, that is, she was at least four months pregnant by this time. Her pregnancy also featured in royal communications. Henry muttered to Chapuys in February that he had no other heir except his daughter Elizabeth, ‘until he had a son, which he thought would happen soon’. There were also instructions issued to Anne’s brother in early July to carry a missive to the French king postponing a meeting between the two monarchs until the following April because ‘being so far gone with child, she [Anne] could not cross the sea with the King, and she would be deprived of his Highness’s presence when it was most necessary’. Finally, a portrait medal of Anne Boleyn was cast, inscribed with Anne’s motto ‘The Most Happy’, possibly to commemorate the expected arrival of a prince: this survives in the British Museum as the only agreed contemporary image of Anne.2

But no child was born. Then in late September 1534, Chapuys sent a strange letter to Charles V after he was reunited with the court after their summer progress. It reads ‘since the King began to doubt whether his lady was enceinte [pregnant] or not, he has renewed and increased the love he formerly had for a very beautiful damsel of the Court’. Sir John Dewhurst, in a study of the miscarriages of Katherine of Aragon and Anne Boleyn, remarked that there was little reason for the king to doubt the queen’s pregnancy unless she failed to go into labour and bear a child. Certainly, a pregnancy that was at four months by April would, in the normal course of things, have been due by late September. Sir John suggests that it was a case of pseudocyesis or phantom pregnancy, which occurs when the stomach swells because a woman is desperate to have a child, even though she is not actually pregnant. Henry’s daughter, Mary, was later to experience exactly the same thing. The alternative is what many historians, including Anne’s most recent biographer, Eric Ives, have concluded – that Anne secretly miscarried or had a stillbirth while the court was on royal progress in the summer months of 1534. Mystery shrouded it because Henry and Anne were keen to conceal it, and the reduced size of the court on progress made such secrecy possible. Yet, this is quite dissatisfying because it means arguing for a miscarriage on the very basis of an absence of evidence. And this is not the usual pattern for Henry’s wives’ miscarriages. For the whole sorry tale of Katherine of Aragon’s miscarriages, and for Anne Boleyn’s miscarriage of 1536, there appears to have been no attempt at concealment, and the court was awash with the gossip. Our primary sources for the 1536 miscarriage are Chapuys, Charles Wriothesley and Lancelot de Carles – in other words, all people who would have picked up the rumours at court. Neither could the royal couple have expected people to have simply forgotten about her rounded belly of the preceding months. Finally, a previous phantom pregnancy would explain the otherwise curious rumours across Europe in early 1536 that Anne’s miscarriage had been a pretence. The bishop of Faenza, the papal nuncio in France, wrote in March 1536 that ‘ “that woman” pretended to have miscarried of a son, not really being with child, and, to keep up the deceit, would allow no one to attend on her but her sister.’ These sentiments were reiterated elsewhere. We just don’t have enough evidence to conclude this with confidence.3

Either way, the m

iscarriage of January 1536 – whether as the first shocking failure or a further nail in the coffin – was a great blow to both Henry and Anne. Wriothesley’s Chronicle states that Anne ‘reckoned herself at the time but fifteen weeks gone with child’, which tallies roughly with Chapuys’ estimate that Anne had carried the child for three and a half months: it seems to have been long enough either way to know that it was a son and heir that had been lost. Did it suggest to Henry, as some historians would have it, that Anne would never be able to bear him a male heir, and that the marriage was doomed? The king was known to have shown ‘great distress’ and ‘great disappointment and sorrow’ at the tragedy. Chapuys gives an account of the king’s visit to Anne’s chamber after hearing the news. He said very little to her, except, ‘I see that God will not give me male children’, and as an afterthought as he prepared to leave, ‘When you are up, I will come and speak to you.’ These sound like the words of one numb with grief. Anne then told him why she thought she had miscarried – that it had been the result of Henry’s fall, and that his love for another woman broke her heart. At which Henry was greatly hurt – whether ashamed of his failings or bitter at her accusations depends on one’s reading – and left her to convalesce at Greenwich while he went to mark the feast day of St Matthew at Whitehall. Chapuys rather maliciously reads into this that Henry had abandoned Anne, ‘whereas in former times he could hardly be one hour without her’. Certainly, both Henry and Anne seem to have been painfully aware of the possibility that history might repeat itself. There is some evidence that Anne worried on the day of her miscarriage that Henry would dispose of her, as he had the last queen. There is also the story that Chapuys reported third-hand, having been told it by Anne’s enemies, the Marquess and Marchioness of Exeter. They in turn had been informed by one of the principal courtiers, who said Henry had spoken to him in confidence. This was that Henry said to this anonymous courtier ‘as if in confession’ that he had made the marriage by being ‘seduced and constrained by sortilèges’, and that he considered the marriage to be null and void, seeing that God had shown his displeasure at it because he did not allow them any male children. Henry therefore believed he could take another wife, which he said he wished to do.4

1536: The Year that Changed Henry VIII

1536: The Year that Changed Henry VIII